There are many myths and mysteries about the Mooney line of

aircraft. The slick design, high speeds, affordable complexity

and luxury end of the small piston spectrum tend to make Mooney's

mysterious, desirable, ladies. Other airplanes appear more accessible

to transition into

and take best care of, the Mooneys have whispered challenges. My

goal in this article is to present the Mooney transition I went

through,

and

hopefully

debunk

some myths while highlighting the accurate positive advantages

of this vintage performance bird.

|

I purchased a 1980 Mooney M20K 231.(read about the

whole purchase process here ),

a Mooney model which carries most of the characteristics I describe

as being Mooney

Demons.Here are my thoughts about the Mooney transition,

and whether the myths became fact. By the way, prior to this

I flew Piper Archers.

As part of the transition, I took 10 hours of dual training

from a very experienced Mooney instructor, well worth it, I strongly

recommend

you do

so. My 10

hours took us through the standard air work (steep turns, stalls),

emergency procedures, and then perhaps the most important 5.5 hours

of the training, landing at 11 different airports in one day, from

high altitude airports like Lake

Tahoe to mountain top strips like

Willits, to big

sea level fields like Sacramento

Executive. |

I'll walk through it as you would take a flight, from boarding

to securing

- On the Ramp and Boarding

- Starting

- Taxi and runup

- Takeoff

- Climb

- Cruise

- Engine operation

- Decent

- Landing

- Conclusion

|

On the Ramp and boarding: One

thing that strikes you as you walk out to the Mooney for the

first (or second,

or

third)

time is that it appears tiny. Mooneys look smaller on the ramp,

something you need to get used to, since you're going to be explaining

to potential passengers that Yes, there is room in there

for you! It sits low. The retractable gear sit the airplane

lower than a Piper, and a great deal lower than a Cessna, Cirrus

and others. Looks smaller, though the (relative) same fuselage

volume has just been set down at a lower level. And the vertical

tail, straight-up-and-down, doesn't lead your eye along. Other

swept tails lead your eye, convincing you the airplane is longer.

Up closer, by the right rear wing root, getting ready to climb

in. Opening the baggage door you notice that it's narrow, and

mounted high on the fuselage. It's

an up

and over load,

not a slide in. Also, the door is curved and doesn't' open

past 90 degrees, so you cannot get something straight up and

in. Be prepared to do a lot of lifting and juggling to get

things in the door.

Climb up on the wing. The 231 does not have

a helper step, so it's a stretch to step over the flap and

onto the walkway.

The doorway is narrower than many, but the door swings wide.

The upper door cutout goes deeper into the skin that, say,

a Piper, so there is a little more maneuvering room.

The seats are inches lower than the door sill, so there is

some contortions to be done to get in. And as the pilot, make darned sure

you slide your seat back fully aft when you get out, or you'll

be banging into cowl flap, vent, and throttle levers as you

worm into the seat.

Seating position: I read about this a bit,

and it turns out to be true and something that takes some time

to get used to. The Mooney rudder pedals are further forward

than I had expected. I'm

not tall,

but

not short, and I have to have the seat almost fully forward

to be comfortable on the pedals. What this means immediately

is that you have a different view of the instrument cluster,

you have a more extreme downward view angle. I had to get used

to a new perception of the attitude indicator,for instance,

to determine straight and level.

Another issue with the further forward seat is the yoke is

much more in your lap. I'll talk about this more when talking

about flying the aircraft, but just sitting in it you realize

that your trusty kneeboard is a lot harder to write on. I'm

moving to a yoke-mounted clipboard to adapt to this.

The width of the cockpit is not the issue some have made of

it. It feels slightly wider than an Archer, and I have slightly

less interference with the passenger

Headroom is not an issue, my headset or hat has not hit the

roof. Now lets gently close the door (do not slam

it, gently close and latch) and start it up.

|

Starting:The 231 is a turbocharged fuel injected model, differently

equipped models will start differently.

There are a lot of myths about starting a turbocharged Mooney,

I read them all and held this issue (along with landing) as the

spookiest thing about transitioning to a Mooney.

Not a Problem. I had the right person show me good technique,

and I've not had any starting issues. Note it's now 2010 and I've revised my starting procedure. What I explained here in the past was good, but this is now better, and works wonderfully well.

First different thing first for those who have flown other aircraft:

Don't turn on a fuel pump. Yes, there are two fuel pump switches,

one

for

low

boost

and

one for

high boost. But during normal operations, from start to takeoff

to landing you do not use the fuel pumps.

Press the electric primer for the period of seconds,. there

is a chart in the POH you can follow if you want. Now, wait. I time 30 seconds from when I stop pressing the primer switch to when I engage the starter. This gives the fuel you just blew in a chance to vaporize. With this technique the engine starts near instantly, even when it's near 30 deg. F. Quickly set to

1,200 RPM, and warm up the oil going to the turbo, be ready to give it a few squirts from the primer switch as you settle it in on 1,200.

The second myth about starting, starting a hot turbo engine,

also turned out to be easy to master with the right guidance. My

transition instructor said;

What has been happening for the last 45 minutes? The fuel

injector lines running on top of the engine have been heated

by the updraft heat while this airplane has been sitting. What

does that mean? The fuel is vaporized in the lines. That's what

causes the hard starts!

Which means the key is to overcome the vaporlock. How? Shove

the throttle in, and hit the low boost pump for 10-30 seconds without cranking

the engine. You're charging the lines and (hopefully) forcing the

vapor to either exit or go back into solution. Then back to the

standard starting procedure. I used this technique after a 1/2

hours start at Lake Tahoe (6,400 ft, density altitude that day

of 8,200) and a 2 hour stop at sea level and it again works without

a hitch. I no longer worry about starting a turbo Mooney.

Everything else is standard, time to... |

Taxi and Runup: Here you may experience the long

throw to the pedals issue again if you didn't slide your

seat forward enough, since you couldn't imagine having to be that close

to the instrument panel! To steer and apply the brakes you sure

do, so stop the airplane and pull up a little more. There are rudder pedal extension kits, I had the 1.5 inch ones installed in 2007 and they help this issue.

When you're taxing you get another difference, and this is Mooney

model specific. Many Mooneys, like M20k, have slightly shorter

instrument panels that many other airplanes. That means you have

a better view frontwards during taxi, which is very nice.

An issue which might just be my airplane first arises here.

The brakes are not as effective as other airplanes I've flow.

I find myself applying more pressure that I expect to have to

apply.

Steering is not too broad, but also not too tight, so watch

your turn to runup position the first few times so you don't

end up with one wheel in the grass.

Park and runup. Nothing new, time to.... |

Take off

Trim is important. And, flap are important. 10 degrees flap at

takeoff is recommended in the POH (though not required). I've tried

a no-flap takeoff in the 231, and I prefer having the flaps down

during TO.

Onto the runway, and roll the throttle up. Acceleration in the

first third of the takeoff roll is less that I've been used to,

but once you are at 40" manifold pressure and get rolling, the

airplane accelerates rapidly. The nose wheel starts to shimmy at

about 61 KIAS, pull back with about 2 pounds of pressure to smooth

out the shimmy, then apply progressively more pressure and she lifts

right off at 64 KIAS. Very smooth initial ground-break to climb once

you've got the feel for it.

Gear up (because you're now a cool Mooney Pilot), not much change.

Take the 10 degrees of flaps up Whoa!!!!!!! Holy

Toledo does the nose want to shoot straight up when you take the

flaps in!

The POH warns you about it, but golly it sure is dramatic

when you first (and 2nd, and 3rd, and 30th) experience it. I now

have the habit of having my thumb putting in nose-down trim when

I start reaching for the flap up switch, you have to stay ahead

of the nose up. Hard to get through your head, because it is only

10

degrees of flaps, and the flaps look so small on the Mooney, long

but narrow.

Note also that the takeoff at altitude was not much different.

I've taken off from Lake Tahoe twice, once with a density altitude

of 8,200 and once with 8,400 with no issues. Of course the turbo

is taking care of the engine in a 231, but the ground roll was

as in the book or less.

So we're.... |

Climbing: The Mooney climbs very well. In fact,

the Mooney climb confuses me.

If I trim to 90 knots, I'm getting 800 fpm. If I trim to slightly

less, a performance climb at 85 knots, I'm getting 1200-1500 fpm.

Drop the nose and climb at 100 and I'm getting 500 fpm or more.

The climb performance is much broader, and better, than I had expected,

it's actually hard because you have so many variables to pick

from. One thing I have not noticed is engine heat

problems on climb. Even at a performance climb regime the engine

stays comfortably in the green temperature band. Don't ignore it,

but it's not stressful.

This has been in 80-90 degree Fahrenheit weather, too, or at

high altitude at Tahoe. I can't wait to see how quickly I can

peg the VSI needle when it's 35 degrees.

Ready to.... |

Cruise Level off and get ready for cruise.

The airplane takes about 5 minutes to settle in to cruise, so

be prepared to tweak your engine and prop settings for a little

bit. Then, first real difference, is pick you speed. At 11,500

I've had comfortable cruise speeds (meaning no excessive noise

or vibe from odd prop or throttle settings and using by-the-charts

settings) between 130 knots and 170 knots. The range of speed

you can pick from makes

a Mooney much different from an Archer, for example, where you

really just want it to go as fast as it can at 75% power. Heck,

I've pushed rented Archer II's at 75% making only 120 knots and burning

9 gph. Setting the Mooney to 130 knots drops fuel consumption

to 6.5-7 gph

So

decide what you want to do, go fast or go still-fast-but-not-so-fast

and go. Now that we've gone up and leveled off, lets talk about... |

Engine Operation: This area really relates

to turbo models of Mooneys, like my 231.

First thing to consider is; If you got an airplane with a turbo,

you'd better fly up high to make it worth it. If your regular

flying regime is below 12,000 ft, you don't need, and shouldn't

get, a turbo equipped Mooney, it's just a waste of weight and

another potential failure point. Read more about that in my Buying

a Plane notes.

If you do need and get a turbo equipped Mooney, there is slightly

more workload. But you'll find it's easy to understand, the differences

make sense, so it's easy to incorporate into your regular operations.

Take-off and going around are the only times when you'll even

think hard about it. A turbo'd Mooney can't be pushed full throttle

(as you've been trained in normally aspirated airplanes) in those

situations, you'll spin the turbo too fast and over pressurize

your engine. Which will make something break eventually.

| This means a good look at the manifold pressure gauge on

a normal takeoff |

|

and getting a good feel for how much extra is left

in the throttle at max allowed manifold pressure. In my 231,

for example, the maximum allowable manifold pressure is 40 inches,

and that leaves almost 1/4 of total travel still left in the

throttle at sea level. Not hard, but you do have to spend that

extra time on the takeoff roll to look at the MP gauge. Doing

a static power-up doesn't really help, as you being the roll

the manifold pressure will change so you have to look anyway.

Go-arounds: So what does that mean during a go-around when your

hands are really busy getting the heck away from the ground,

and looking to the side at the MP gauge and doing finicky, precise,

throttle movements could put you at risk of losing control. Relax! First,

the POH gives you a little bit of flexibility, most turbocharged

engines can take some overboost. The 1980 231 can handle a transitory

manifold pressure of up to 43 inches for less than ten seconds.

Sounds too short? No, that's about the time it takes to settle

into the climb phase of a go-around, so even if you do slam the

throttle forward on a go-around you will probably un-boost before

it becomes an issue. Second, after a few flights you have a feel

for where the throttle is, anyway, and you probably won't push

the throttle full in anyway, so the max you'll overboost may

be a half-inch, which you can quickly fix.

Once you're in the air, you can drive yourself crazy if you

try and fix manifold pressure settings quickly. The key in a

turbo'd Mooney is: Make small adjustments, and let it settle

out. Wait at least 10 seconds to see the result of your throttle

adjustment before you make another one.

Bootstrapping.

Some turbo'd aircraft experience fluctuations in manifold

pressure that makes them hard to coax into cruise, commonly

referred to as bootstrapping. You can find better explanations

elsewhere on the Web, but basically some aircraft have to be

managed carefully to insure that any altitude change doesn't

result in a manifold pressure change which causes a power change

which causes an altitude change which causes a manifold pressure

change which causes a power change which causes an altitude

change which....you get the idea. I have not found my 231

to be susceptible to bootstrapping. I think it's because the

damned thing takes so long to settle in to a new power setting

that it can't react fast enough to transitory pressure changes. Admittedly, I have a Merlyn automatic wastegate which also makes bootstrapping more unlikely.

Engine temps: All my flights over one

hour duration are at 15,000 ft or above, with my preferred

altitude being 17,000 ft. and I

have not noticed particular issues with high altitude heat-shedding.

17k and outside air temp of 0 C (which is warm at that altitude)

results in temps that are in the upper half of the green bands,

but still well away from the red or yellow. I've also taken her up to ceiling going East, 23,000 ft., but rarely, just to avoid weather. Up that high the engine does teeter on the edge of the yellow, even with a -25 dC external temp reading, so be very mindful above 20,000 ft.

Leaning: I lean by the POH, which is rich-of-peak. Others run

lean-of-peak. You choose. I have run my engine LOP to see if it could handle it smoothly, and it can. |

Control The myths say Mooneys are heavy at the

controls. My experience indicates, yeah, they are. Takes some effort

to yank the yoke over, takes a lot of effort to push the nose up

and down out of the trimmed position.

Roll is heavy to start, and once it starts it wants to continue,

so be ready to neutralize almost as soon as you move into a maneuver.

That can catch you a little off-guard the first few times since

you had to throw so much energy into it to start the roll that

it's a little disconcerting to have to catch it so quickly.

Pitch, learn to use that trim switch. I've stopped using the

yoke for most pitch movements after the wheels leave the ground

until they touch back down again, it's fly by trim. And in cruise

flight I switch from using the

trim switch to using the trim wheel, because you want to make very

very small trim adjustments when you're settling into cruise.

This isn't bad, by the way. The heaviness of the controls

means it is a very stable cruise platform. I've gone through some

moderate turbulence and she stays rock-solid in pitch and roll.

Another indication of this is in stall recovery.

First, damn, it's very very hard to stall this airplane. Second,

once you do stall it do any one thing right and she pops

out of the stall. Bump the throttle up a little, she pops out of

the stall. Drop the nose an inch, she pops out of the stall. On

my initial two stalls my recovery technique was horrible, but the

airplane

broke

the

stall

in seconds

anyway.

I'm not implying that the airplane isn't fun to fly. It is,

and you can crank her over on a wingtip and have some fun. But

it is heavier to move that others.

With the full forward seating position, the yoke is more in

your lap than on other airplanes, and this takes a little getting

used to. Your pivot point for your left arm for roll is different,

adjust. Pulling back on the yoke you're starting with your arm

almost at 90 degrees at the elbow, vs. stretched out somewhat

in other airplanes, so you might find you need more muscle to

pull it back.

A little later note here: I've started sliding my seat a notch

or two back when I enter cruise. I don't need to reach the toe

brakes anymore, and two notches back gives me more room for my

kneeboard and yoke, and gives me a more neutral view of the instrument

panel. I still have excellent rudder control a little further

back.

Enjoying the ride

So how is the ride? Pretty great!

The visibility is excellent. I mentioned the lower instrument

panel, forward visibility is very good. The view from the pilot

and co-pilot window is better that a Piper, feels like you're

a little further around the curve of the fuselage. The

wing root is also further back relative to the pilot window and

position, so you can see more directly down. I can actually see

airports the GPS says I'm flying directly over. The rear passenger

windows are also very big, and you can see much farther to the

rear quarters of the airplane in flight, I've found this really

enhances my ability to see aircraft behind me when I make a turn

or in the pattern.

Noise: Probably an issue, but fixable. The Mooney I have has

an inflatable door seal, and the door seal really quiets the

cabin down. When I have forgotten to inflate the door seal the

cabin has been quite loud (even with my Bose X noise cancellers)

so I suspect a non-sealed cabin is noisier than a Piper/Cirrus.

Body comfort: The first thing my partner said when

we sat in the airplane before we bought it was "Wow,

this legroom is great!" and that continues to be true.

You have more legroom in a Mooney than any other airplane I've

ever ridden/flown, and your passengers will appreciate it. My

1980 has stock, untouched seats and they still feel very comfortable.

The longest I've flow the Mooney at one sitting is 4 hours, but

in that time I found no discomfort hotspots.

Bounce and jerk: Again, the Mooney is a very stable platform.

It smoothes out the turbulence that might make another airplane

uncomfortable. I've encountered severe turbulence once, departing North Las Vegas airport when the winds at 6,000 ft. were 65 knots and bubbling all over the mountain ridges. Very rough ride, with my head hitting the roof of the airplane. But I never felt the airplane was out of control (I may have been out of control of it), very stable even when it was being bounced all the heck over.

Crusing is over, time to.... |

Decent. The entire internet is paranoid about

the decent and shock cooling of a Mooney, particularly

a turbocharged Mooney.

Before we get into the realities, a little rant: As a former

aerospace engineer and a damned good mechanic before that, what

most

people

are

referring to as shock cooling is a very questionable

phenomena as described. i.e., y'all have not idea what you're

talking about,

do some reading and get some practical experience in materials,

engines, heat exchange, and common sense, before you start

flapping your yaps.

Until then shut up about topics you obviously

only have half a clue about,

like shock

cooling,

since your only goal is obviously to panic people who don't

understand with expositions of your great knowledge. You're

actually putting those poor folks at greater risk since they

may hesitate when they need to do the right thing for safety of

flight because they are terrified of shock cooling.

For those folks who are just flying their Mooney's, relax.

You are not going to cause irreparable damage to your engine

by reducing

power

at

the top

of a decent.

Just use good common sense, and think of this as an engine

longevity extender, not something mysterious.

Simple enough: When it's time to descend you don't slam the

throttle closed, you reduce speed slowly to insure that all the

parts of the engine, and in some Mooney's cases particularly

the turbocharger, cool evenly and at a relatively gradual rate

to insure the greatest engine life.

The Mooney transition means that you have to be a little more

aware, well, a lot more aware, of when you need to start your decent,

plan to start quite a bit further out than you would in other

airplanes.

The

things

we buy a Mooney for, like speed and speed mean

that you are (1) going to cover a lot more ground as you descend

and (2) are going to have a shallower decent rate unless you chop

the engine abruptly. Also, if you're flying a turbo,you'll find

yourself regularly flying above 10,000 ft., since the engine will

keep performing

all the

way up. I've added about 5,000 ft to my regular cruise altitudes

over Pipers, and that means 5,000 additional feet to descend, and I'm

traveling 30-50 knots faster, so I have to add 10-15 more miles

to my decent profile to descend at an ear-comfortable 500 fpm.

It's 2012 now, and I want to add something else here that's been true the whole time but I haven't explicitly mentioned. This airplane does not want to slow down. The hardest thing I have to do when I'm on my typical flight to Boise, descending out of 17,000 ft. for the 2,800 ft. msl airport is slow this baby down. Pulling the throttle back will get you down to 150 knots pretty quickly. But at that point she does not want to go slower. Basically I'm back on the throttle to 15-17 inches of MP with a bunch of nose-up trim to get down to my gear speed of 130 knots. She just does not want to stop flying.

Once the gear is down it's a little easier to slow more, but even then it's a challenge to slow. Be prepared.

Plan the decent's and watch your temps. My transition trainer,and

the POH, suggest reducing the prop RPM to lowest governable during

some portions of the decent, this tends to lug the engine, which

keeps the engine cooling more slowly and keeps final temp above

minimum. Drop your manifold pressure to descend, reduce prop speed

to keep the heat up, and it works out well.

Of course, you can take the cheaters way like I did and get

speed brakes installed. Precise

Flight speed brakes take a 400

fpm decent and change it with the push of a button to a 1000 fpm

decent, while still maintaining the same engine performance.

In

other words, you're descending faster but are still keeping power

levels up so you both keep the engine warm and keep yourself

on the forward side of the power curve, giving you more flexibility

in case of emergencies. I strongly recommend the speed brakes

for

a Mooney. I've even landed with them deployed on a calm, empty

day at the airport to insure I could manage it in case of an

up failure, it was a non-event. They are very handy.

Of course, somewhere during the decent you have to... |

Land. The final huge Mooney myth is that they

are hard to land, that they will float forever.

Confirm, gear down, gear green light on

There is truth to this myth, but it's a simple fix that we learn

in any airplane we fly.airspeed on approach. Watch

your airspeed, and a Mooney lands as easily as a Piper or a Cirrus.

The book airspeeds seem to work just fine

Confirm, gear down, gear green light on

In fact, the best landing I've ever done (in 461 landings) was

in my Mooney,after 20 landings I had the airspeed drilled into

my hands and it just settles right down on the runway.

Confirm, gear down, gear green light on

Higher speed does make it float, but dang it, a Piper floats

too. What I find in the two "too high approach speed

goarounds" I've

done is that in the Mooney you're not tempted to take the high

approach into the runway, you know the beast is going to just

float and float, so you go around like you should. In a Piper

I've forced it to the ground, with ensuing bouncy bouncy. The

Mooney

float

should

make you a safer lander.

Confirm, gear down, gear green light on

Flaps: First, remember the nose-up I mentioned when you pull

the flaps up after takeoff? When you start feeding the flaps

down for landing you get the opposite, the nose starts going

down dramatically. My habit is now, similar to take off, start

rolling

the trim

nose-up, then start moving the flaps down, trim trim trim, no

hand movement of the yoke, takes care of it well. I've landed

no flaps, partial flaps, and full flaps. And full flaps with

speed brakes extended (to see how controllable it was). I don't

find the difference between 10 degrees of flaps and full, 33,

degrees of flaps to have much effect on the landing process,

others might feel differently. Just slide down 10+ degrees and

land.

Confirm, gear down, gear green light on

Confirm, gear down, gear green light on. Gear comes up, gear

gotta go down. New habit for the transition to a Mooney, check

ever 10 seconds to insure the gear is down. Turn downwind, check

gear down. Base, check gear down. Final, is the gear down? Have

your passenger ask you if the gear is down. Don't land with

the gear up! It won't actually cause as much damage as you

might think, but heck you don't want to tell

people you landed with the gear up! A mechanical failure is one

thing, but I forgot should not happen.

Over the fence, 70-75 knots, pull power back. I'm still in the

air, so I'm still controlling pitch with the trim button, not

with pressure on the yoke, roll the trim steadily back as the

runway gets closer, hand on the yoke to flare, then more trim

as she settles down. Stall horn, chirp it's down. I

open the cowl flaps as soon as that happens, just so I don't

forget.

Here again it might just be my airplane, but it might be all

Mooneys, the brakes aren't as strong as other airplanes, so you

might find yourself rolling past the taxiway exit you usually

take. My experience has been that I use less runway

to land with the Mooney, but I use more on the landing

rollout.

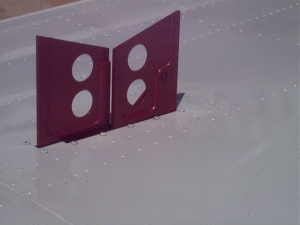

Another area that transition reports mention is the different

feel of the landing because of the shock disks (the black rubber

disks

in the picture above) instead of a bungee/spring (Cessna et .al.)

or oleo struts (Piper et. al.). Some report that the shock disks

rebound more strongly, causing the airplane to potentially bounce/porpoise

more easily. I have not noticed that, and again, airspeed is

the key, with the right airspeed the shock disks and landing

feel normal.

Crosswind landings appear to be a non-issue. I've landed, so

far, in a 14 knot perpendicular crosswind without noticing any

handling changes except a slight drift sideways over the runway.

Tonight, for example, the Cessna on the parallel runway kept

asking for wind updates on the crosswind while I barely (and

I mean barely ) noticed that there was a crosswind.

TImer starts for the 4-5 minute Turbo cool down, and we taxi

back to the spot.

A note on Speed.

One question that has come my way a few times since I posted this

is concern about a Mooney's speed if you have spent most of your

time in slower speed aircraft. Will the higher speeds, 30-70 knots

faster than trainers, cause me trouble?

My simple answer has been no, you'll just enjoy the

speed. But today, when someone again asked this, I thought about

it more than superficially, and there is a real reason why you

should not be overly concerned about the speed boost you'll get

in a Mooney, even if you've been putting around the sky at 111

knots in an Archer, like I was.

Let's think about speed. Where does a Mooney give you speed?

My Mooney is 65 knots faster in cruise than the Archers I learned

on. In Cruise. When you're straight

and level. When you usually have time to handle whatever ATC is

going to throw at you. That's good speed, speed that you

don't have to worry about, just use.

What is speed that you worry about? Takeoff and landing, right?

Those are generally the times when you are the most busy, and

the most likely to get behind the airplane (of course, approaches

for IFR pilots). So how does a Mooney compare with an Archer

during those critical times.

Well, I rotate my 231 at the book speed, 64 knots (well, 65

since it's easier to see). Let me look at a Piper PA-28 POH and

see what the rotation speed is...Hmmm, 52 to 65 knots. Technically

the same as the Mooney!

Well, how about landing? I usually strive for 65 knots on short

final for a greaser landing. What does the PA-28 want your speed

to be on short final? Section 4.2 Landing Final Approach

Speed (Flaps 40 degrees) 66 KIAS . Well look at that, the

PA-28 is actually a knot faster than the Mooney on landing!

It's in black and white, the speed difference in the most critical

segements of flight between my Mooney 231 and a trainer-type

Piper Archer is non-existant!

It's true, getting down to those speeds is a bit tougher because

the Mooney wing wants to keep going fast. But most of your training

will transfer, your speeds and sendse of movement across the

ground on landing, for example, will be identical in

a Mooney!

Don't worry about speed, just look forward to the 50 knots more

in cruise. |

Conclusion

Mooneys are looked at as unusual beasts with

mythic gotchas to eat you. I hope, if you're planning

to start renting or buying a Mooney, that I've covered the Mooney

myths you are worried about.

I'm very very pleased with my purchase of a Mooney. It delivers,

it actually over delivers, on the promises you have heard about,

speed, range, economy, while not being the cantankerous

pilot-eater you might be fearing. Find a good transition instructor

(I can recommend mine if you're in California), read the POH and

follow it, and treat the airplane like a precision piece of machinery,

and you will not meet the myths.

Hope this gave you some insights, please send me any feedback

C.K. Haun

|

| |

A Year later Everything I wrote

above continues to be true, and now I've added an IFR ticket

to my certifications. That meant about 45 hours training

in 3636H (0 hours in a simulator) and I can categorically say

that a Mooney is a fine IFR platform. Couple of things to mention

about flying a Mooney IFR, in my view:

- Speeds and sink rates. Once you know your bird, establishing

and maintaining decent rates and power settings for approaches

is easy. In my case, again, adding speed brakes makes approaches

much easier and more controllable.

- Stability. Mooneys are stable. Any divergence from straight

and level that you induce while looking at an approach plate

or other distractions happens very slowly and almost predictably.

In 45 hours under the hood and real IMC my instructor never

took the controls to prevent an upset. I'll admit, part of

this is because my instructor is a very experienced

Mooney pilot himself, so he may have let some things go further

than another instructor would have.

- Instrumentation. One area that still gives me some concern.

The close-in seating position, as mentioned above, really

doesn't give me a great perspective on the Attitude Indicator.

Since you're close in you feel like you're looking down on

the instrument, instead of straight at it. This doesn't affect

horizontal awareness, but pitch up/down is harder to tell.

Seeing how many dots up or down you are pitched to takes

practice, and a weather eye on the HSI and altimeter. Part

of this also is that I have a flight director with the delta

shape to look at, instead of the more traditional wing and

dot indicator. Other instrumentation is just fine, and the

Garmin 530 makes IFR approaches almost too easy. Heck, it

tells and shows you procedure turn angles, tracks times for

you in holds, and gives you every sub-arc of a DME Arc, and

ATC will just aim you at the middle of the arc if you're

/G .

- Control. On an approach, the Mooney is very easy to track

straight (well, after 30 hours of trying). Once the needle

is centered, very small control inputs keep you centered,

and on an ILS inside the marker it's just little bits of

rudder and you're on your course.

- Getting there. The other thing about a Mooney in the IFR

system is that you've got speed. You can zip between approaches

at 140 knots while you're practicing, and on the outer segments

you can keep your speed up enough to please the most harried

controller. Then drop the gear, dirty it up, pull the throttle

back, and it's an easy 95 knots to the FAF.

- Turbulence. IFR means bumps. Mooney's handle turbulence

very very well. The stability mentioned earlier shines in

bumps.

And that's it. A great IFR platform. |

| |

|